In this article, Ian Marsh argues that ‘family wars‘ in business are different from commercial disputes, explains why and suggests how the mediation process can be adapted to deal with very differing needs. It is based upon a seminar given to the Hong Kong Mediation Council on 10 November 2010.

Introduction and context

“I have come to believe that people communicate more effectively, make better decisions, and deal with their differences more constructively, if they set aside their assumptions and engage in open, honest, dialogue on matters of common concern.”1

It is said that some 70% of large, and 90% of medium-sized, publicly traded companies in Hong Kong are in family control, with a member of the controlling family serving as CEO, Chairman, Honorary Chairman or Vice-Chairman of 86% of those enterprises. Many are still controlled by their founders and are facing succession issues at both shareholder and board level2.

Globally, it is estimated that 70% of business succession plans fail, in the sense that they end with an involuntary loss of control of the assets concerned3. That failure rate appears to be consistent across jurisdictions, and regardless of tax rates and the economic cycle.

Further research4 suggests that 60% of those failures are caused by a breakdown of trust and communication within the family, and 25% by a failure to prepare the next generation for what awaits them; the latter is itself often a failure of trust and communication. Only 15% of failures appear to relate to the ‘hard issues’, such as failed tax planning, structuring, or investment performance, to which most families and their advisors generally pay most attention.

Whatever the cause, it is likely that a significant number of those succession failures will result in internecine warfare within the family, which so often destroys not only the business, and all the economic activity it generates, but also the lives and relationships of family members.

However lawyers might frame them, the majority of such disputes present as arguments over ownership and control and/or the performance of individuals within the family business system.

Family business dynamics

The underlying dynamics of family businesses are many and varied …

Children may press their parents to take things easy and to hand on to the next generation or, increasingly since the collapse of Lehman Brothers, parents may press their children to ‘step up to the plate’ and secure the parents’ pensions. Siblings battle for the top spot, or sometimes to avoid being chained for life to what they see as the family millstone. Those who run the business may see themselves as sacrificing their lives for the sake of the family, while their ‘investor’ cousins are free to live as they will; the investor cousins may regard those who run the business as overpaid and underperforming. Even those with no financial interest in the business, but who share ‘the name’, can find that name an enormous burden. Likewise, the brand may be challenged where the tabloids are full of the social antics of disconnected family members. Finally, non-family executives are routinely hired to run the business, only to be fired for failing to manage the family dynamics.

Of course, nothing is ever about what it’s about. Most people in conflict also have concerns about the impact of that conflict on their relationships with others, on their own self image (threats to which often reflect as guilt in individualistic cultures and as shame in collectivist cultures), as well as their need for

fair process (whatever that may mean to them). Indeed, within business families, issues of relationship and self-image often loom large, as family members struggle to balance the need for them to integrate within the family system with their own need to differentiate themselves from it, to individuate.

These are not contractual relationships, rational relationships of choice, but emotional ties of the deepest kind. They cannot simply be terminated ‘on reasonable notice’. Many people can have little or nothing to do with the rest of their family and be quite comfortable with that. Others cannot. Indeed, for many, the relationship that dominates their lives is too often the one that is most dysfunctional; the one with the person from whom they are most estranged. Examples from the author’s experience include:

(1) a mother whose son had pushed to take over the business and who was convinced the real problem was her failure as a mother to teach her son right from wrong;

(2) sibling rivalries going all the way back to nursery days – one client (who had been attacked by his brother over his performance as a director) criticised his brother for spoiling playtime at the age of four and continued in a similar vein for the next couple of hours in bringing the narrative of the relationship up to the present date (at the age of 42).

Who is ‘family’?

Then there is the whole question of who is ‘family’? For some, it is bloodline only. Their sons – and daughters-inlaw may be greatly loved but they are not at the table when important issues are discussed and decisions made. If the in-laws come from a different culture, this can impose enormous strains, particularly if – as they tend to – they have a material affect on their spouse’s views!

When half-siblings argue, not least over their inheritance, the children of the first union are often driven more by unresolved issues from their parent’s separation and divorce (which, if they were very young at the time, they may well still feel was their fault), than by anything else.

Trigger events

Trigger events are also significant in causing family disputes to ‘go critical’. Such events, very often a death or divorce, also tend to produce deep states of grief which, while different for each family member, will almost certainly ensure that none of them is in a fit state to deal well with the conflicts that follow for some time to come.

Emotions and perceptions

Despite his legal background, the author believes that this emotional context, more than anything else, differentiates family wars from commercial disputes. Whilst all conflict is emotional, some of it intensely so, within families that emotion is rarely generated by the ‘hard issues’ that are presented for resolution.

There is more to it than that, however. Psychologists and neurologists now seem to agree that each of us experiences the world very differently. Schacter5 argues that if it were possible to ensure that two people had exactly the same sensory inputs and emotional experiences for a period of time, their memories of that period would still differ vastly, unless their entire past lives and their personalities were identical (which is most unlikely). Yet, for most of us, that is utterly counter-intuitive. Most people might say that the more time we spend together, the more shared experiences we have, the more alike our world views should be.

Perhaps the pain of family conflict is so exquisite because of this bewildering mismatch between the expectation and the reality of people’s most fundamental emotional relationships.

What does all this mean for the mediation process?

The influence of pressure dynamics in litigation

In the author’s experience, the vast majority of family wars that have been mediated have followed the civil/commercial (ie one-day, last best chance for peace, pressure cooker) model. This is probably for no better reason than that such cases initially arise in civil litigation, most of the available mediators are trained as civil/commercial mediators, and those engaging them usually ask no more than, for example, “when can you do a one-day mediation in the next four weeks, and what will it cost?”

By definition, this suggests a time limited process. The imminence of a deadline, which if missed likely means years of litigation, may often lead one or other party to make the breakthrough offer. However, whilst the pressure of a deadline is a useful tool and should be used when appropriate, to do so as a matter of course is to waste the promise of mediation.

Disputes also tend to be lawyer, rather than stakeholder, led, with a perhaps inevitable focus on the ‘hard’ (typically distributive) issues. The ‘moderating’ influence generally comes in the form of litigation risk analysis, with ‘litigation lost’ and ‘litigation won’ typically being taken as the best and worst alternatives to a negotiated settlement.

Whilst it must be accepted that success rates, at least in terms of litigation settled, reflect those in other areas, too often, in the author’s experience, the real issues between the parties are simply left unattended or at best postponed until the next eruption, whether in this generation or the next. So, the author has come to believe that this is not necessarily the best to way deal with these situations.

How may mediation benefit family business disputes?

(1) Storytelling

Storytelling lies at the heart of mediation. It is often only when people truly feel heard that they realise for the first time what is most important to them, and why. They can begin then to see whether they can meet those needs without input from others. If they can, the conflict is moot. If not, the realisation that they are dependent on others can have a profound effect.

(2) Building trust

Being heard also engenders trust. All mediators use this to build rapport with those with whom they work. Trust may, however, be fungible: those who come to trust the mediator may then appear much more open to trusting those others with whom they are in conflict, at least if the third party is there to facilitate.

(3) Interdependence and dialogue

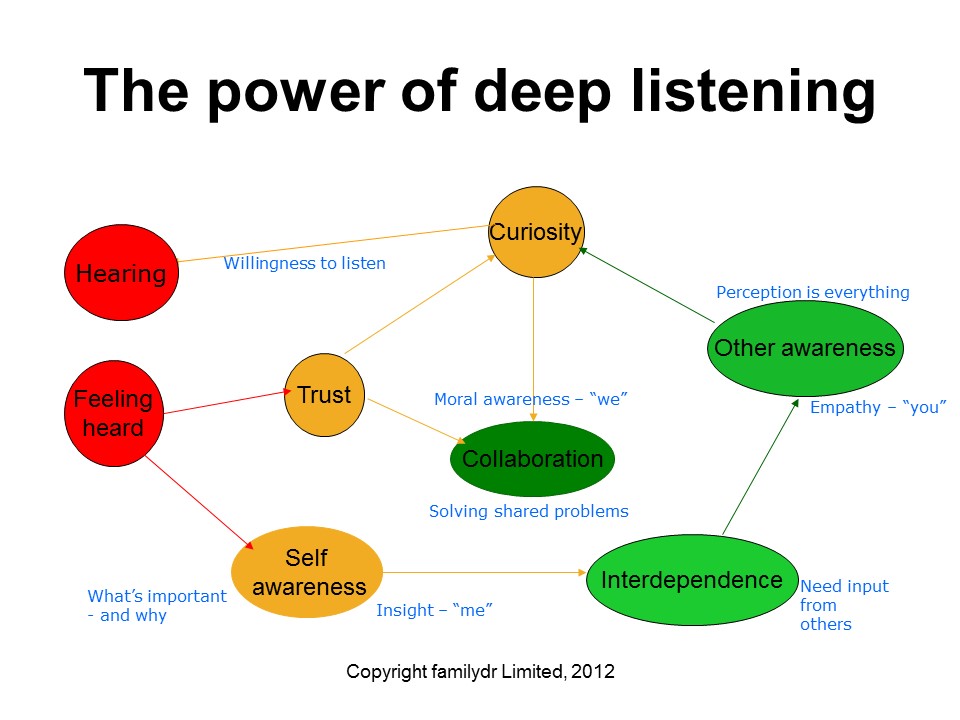

The realisation of interdependence, with a willingness (however reluctant) to trust, opens the way to dialogue, meaning an exercise not in persuasion but in curiosity as to why the other party sees the world so differently, and to discover what is most important to him or her, and why. And so it goes on: I am heard, therefore I listen; I need your help to meet my needs, as you need mine to meet yours …

(4) Deep listening

To feel truly heard, however, most people need to be able to tell their own story, in their own words and in their own time, to someone who has no agenda but to understand what they have to say, and who will accept them for who and what they are, whatever they say.

In this quest, the author draws heavily both on Cloke’s ‘Zen of Mediation’ (being as empathetic as possible, without losing oneself; being as honest as possible, without being judgmental; and being as committed as possible to revealing choices, without caring which (if any) is chosen)6, and on Rogers’ client-centred approach to therapy (facing the problem; the listener being himself, not playing a role; having an unconditional positive regard for the speaker; and empathetic understanding)7. The author calls this ‘deep listening’.

Practical problems and possible solutions

To do all this within a one-day mediation is, however, almost impossible. Consider a ‘simple’ three-party dispute (but bearing in mind that family wars often have many more, generally with constantly shifting alliances). Each party is invited to tell his or her story in private session. To do so fully, one will often need two hours or more, another perhaps 90 minutes, and the third may (or may not) need 40 minutes. Thus, it is quite possible that one party will be sitting, brooding, in his room (and counting the cost of his lawyers!) for four hours or more before being involved in the process in any real sense. That alone does not bode well for a resolution. It should also be remembered that family wars often involve the elderly and infirm, and many who have never been in a meeting lasting longer than ten minutes, let alone a process taking on average ten hours.

On the other hand, if storytelling is curtailed so that the process may be completed in one day, some parties may not feel heard. They may conclude that, whatever the process is about, it is not about them, and the likelihood of the real underlying issues emerging (let alone being addressed) diminishes hugely.

The approach developed by the author in recent years has been to meet with each stakeholder, one on one, at a time and place where they feel comfortable and where they can be the sole focus of attention.

The meeting may commence with no more than the question “so, how do we come to be here?” The author listens deeply for as long as they need to speak, interrupting as little as possible, whilst using all the usual effective listening techniques to confirm that the stakeholder has been understood. However, the author focuses more on the emotions that emerge than on what is expressly complained of, and explores what it was that provoked those reactions,and why that might be. Some parties may find this difficult to begin with, and so may be invited to explore the emotional aspects as a paper exercise post-meeting.

Once all stakeholders involved have been met, consideration needs to be given as to what else needs to be done before they are each going to be ready, willing and able to come together in a facilitated family meeting, the purpose of which will be to have the difficult conversations they have been putting off (or storming out of), sometimes for years.

Occasionally, smaller meetings are needed first to address particular issues. Those who cannot get past their assumptions as to the motives of others may be asked to write down, say, five reasons why someone in the other’s circumstances might do the things they did. Others may need coaching, perhaps some role-play, before they feel able to say what needs to be said; and so on.

Family meetings, when they finally take place, are always fascinating. They usually comprise only the family members and the third party, with a minimum of furniture (no tables to hide behind) and a box of tissues. The author’s approach to rules of engagement is often quite prescriptive: for example, “I” statements only; reactions to what was said or done by another party must be explained rather than

taking the form of accusations as to the other’s intent; listeners will reframe what they have just heard if called upon to do so, etc. The goal of the third party is to speak as little as possible and to allow the family’s dialogue to develop naturally.

The author’s most recent family meeting lasted some four and a half hours, during which he spoke for less than 20 minutes (including rehearsing the rules of engagement, which had previously been agreed to by all). It is interesting to note that, after a couple of interventions, the family members themselves usually take over enforcing the rules where necessary, defusing threatened walk outs, and so on.

Where possible, the family meeting is a lawyer-free process, though the litigators may be on standby in case it fails. As in the divorce mediation process, if issues arise in the course of a meeting upon which parties need advice, it is rarely a problem to organise it. In the author’s experience, however, it is unusual for the hard issues originally presented for resolution even to be mentioned in the family meeting. Once communication has been restored, they often fall away completely. If not, the family members can generally proceed to resolve them by themselves.

All of which just goes to show that, with families at least, it is never just about the money.

1 Comment by the author at the Hong Kong Mediation Council seminar.

2 R la Porta, F López de Silanes & A Shleifer, Corporate Ownership around the World, Journal of Finance 54.2 (1999) 471-517.

3 The New Wealth of Nations, The Economist, 16 June 2001, p3ff; R Beckhard & WG Dyer, Managing Continuity in the Family-Owned Business, Organizational Dynamics 12(1) (1983) 5-12 (American Management Association). Independent research commissioned by the BDO Centre for Family Business has concluded that in the UK only 24% of family businesses reach the second generation, and only 13% the third: see T Bogod, P Leach & R Merson (Eds), Across the Generations: Insights from 100-Year-Old Family Businesses (2004, London: BDO

Centre for Family Business).

4 RO & Williams & V Preisser, Preparing Heirs: Five Steps to a Transition of Family Wealth and Values (2003, Bandon, Oregon: Robert D Reed Publishers).

5 DL Schacter, Searching for Memory: The Brain, the Mind and the Past (1997, New York: Basic Books). See also AR Damasio, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain (1996, London: Vintage Books).

6 K Cloke, Mediating Dangerously: The Frontiers of Conflict Resolution (2001, San Francisco: Jossey Bass).

7 CR Rogers, On Becoming a Person: a therapist’s view of psychotherapy (2004,

London: Constable & Robinson).

First published in Asian Dispute Review, January 2011: 24-27